ABOUT BOWEL CANCER

Anal cancer

While colon and rectal cancers can be similar and are often referred to collectively as colorectal cancer, anal cancer is different in significant ways, including the cell type where cancer begins, the cause of the cancer, who gets this cancer, and how it is treated. Most patients diagnosed with anal cancer do not need surgery, just radiation therapy. Most anal cancers are related to the human papillomavirus (HPV) infection like cervical cancer.

What is anal cancer?

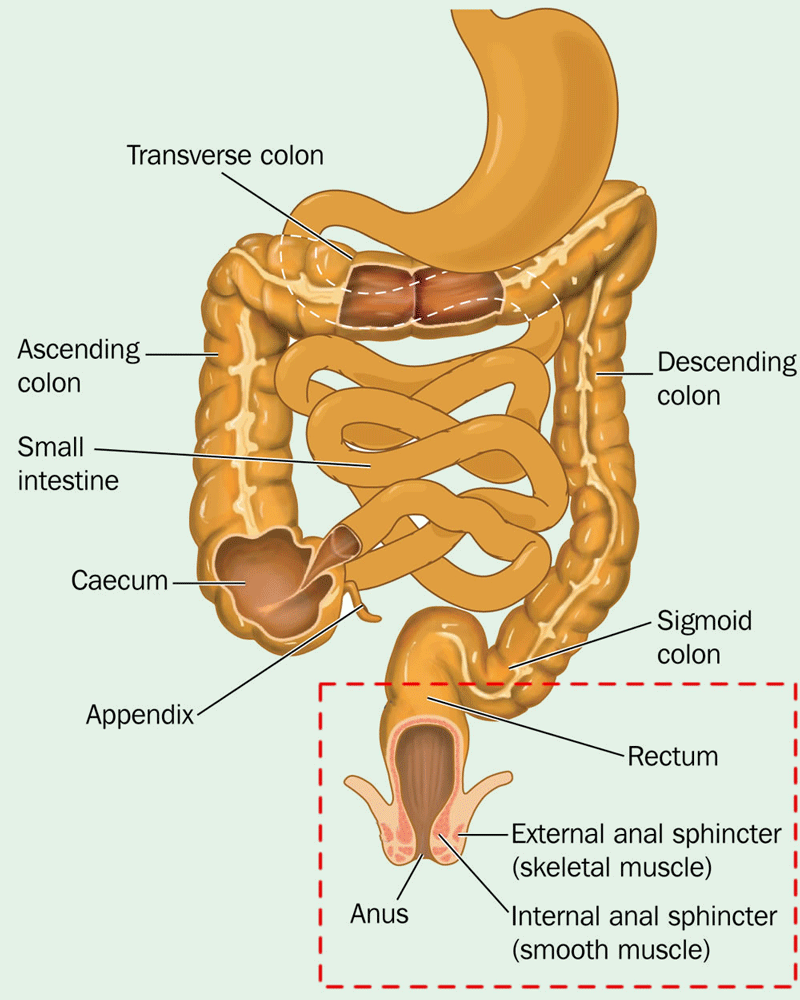

The anus is the final 4 cm of the large bowel that opens to facilitate defaecation. While abnormal cells in the anus can sometimes be harmless, they may progress into cancer. Anal cancer is highly treatable if detected early, and the outlook for patients with anal cancer is often better than for other types of bowel cancer. Precancerous and cancerous changes in the anal canal are similar to cervical cancer.

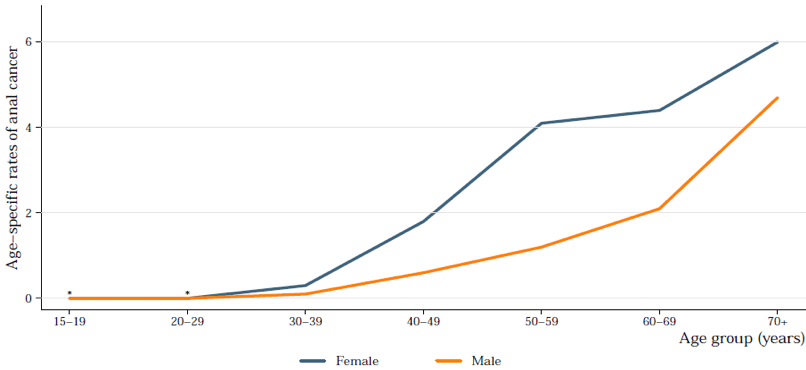

Anal cancer is rare and accounts for less than 0.2%* of all cancers diagnosed in New Zealand. Around 72* new cases of anal cancer are detected each year in New Zealand and age is a significant risk factor in its development. In 2015, no cases were reported in New Zealand for people under 29 years and the highest rates were seen in the 70+ age group. After age 50, anal cancer is slightly more common in women.

*2020 statistics from International Agency for Research on Cancer

Age specific rates of anal cancer

Types of anal cancer

Anal cancers are defined by their location, and the type of cell from which they arise.

- Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common type of anal cancer (about 75% of all cases) and arises from the cells lining either the anal canal or margin (the edge of the anus partially visible outside the body).

- Cloacogenic (basaloid) carcinoma is a subtype of squamous cell carcinoma that develops in the transitional zone (cloaca) and involves a distinct type of cell that differs from squamous cell carcinomas in the anal canal or margin.

- Adenocarcinomas derive from cells in the glands surrounding the anal area. This type of cancer, also known as Paget’s disease, is less common and can also affect the vulva, breasts and other areas of the body.

Other types of malignancies can occur within the vicinity of the anus. These often require their own specialised treatment approaches which may differ to those used for anal cancers. These cancers include:

- skin cancers including basal cell carcinomas, mucosal melanomas, and malignant melanomas

- lymphomas

- gastrointestinal stromal tumours

- Karposi’s sarcoma

Anal cancer risk factors & symptoms

The exact cause of anal cancer is unknown however, there are several factors that may increase the risk of developing the disease, including:

- persistent human papilloma virus (HPV) infection (the virus responsible for genital and anal warts) is thought to have a role in almost 90% of anal cancers

- smoking tobacco

- a history of cervical or vaginal cancer, or abnormal cells of the cervix, which may also be linked with HPV or smoking

- having another condition, or receiving treatment, that suppresses your immune system (e.g. human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection, organ transplantation)

- receptive anal intercourse (anal sex)

- anal fistulas (abnormal openings between the end of the bowel and the skin around the anus)

- frequent anal redness, swelling, and soreness

- old age

Symptoms of anal cancer can include:

• Bleeding from the bottom (rectal bleeding)

• Itching and pain around the anus

• Small lumps around the anus

• A discharge of mucus from the anus

• Loss of bowel control (bowel incontinence)

Detecting and diagnosing anal cancer

The following tests and examinations are commonly used to detect and diagnose anal cancer:

- Medical history and physical examination: your doctor may review your full medical history for cancer risk factors and perform a physical examination to check for signs of cancer. More invasive tests are required to confirm the diagnosis, if anal cancer is suspected.

- A digital rectal examination: your doctor will insert a lubricated, gloved finger into the lower part of the rectum to feel for lumps or anything else that seems unusual.

- An anoscopy or proctoscopy: this procedure examines the anus and rectum using a short, lighted, lubricated tube, allowing the doctor to observe the lining of the anus and to take biopsies if needed.

- A biopsy: a sample of tissue is taken from the suspect area(s) and the cells from the sample are reviewed by a pathologist using a microscope.

- An endo-anal or endorectal ultrasound: an ultrasound transducer (probe) is inserted into the anus or rectum. The probe sends out high-energy sound waves that ‘bounce’ off internal tissues and organs to form a picture of body tissue that can be examined for any abnormalities.

- Blood tests can detect reduced red blood cell counts and analyse changes in liver/kidney function.

Treating anal cancer

The method of treatment for anal cancer depends on the characteristics of the tumour and the individual. Anal cancer may be treated using one, or a combination, of the following treatment options. Your doctor will discuss treatments with you to determine what is best for your circumstances. Treatment options may include:

- Surgery: the tumour is removed from the anus along with some of the surrounding healthy tissue in an attempt to ensure that no cancerous cells are left behind (local resection). In more severe cases, it may be necessary to remove the anus, the rectum, and part of the colon and patients may require a colostomy bag post-surgery.

- Radiation therapy: high-energy X-rays or other types of radiation are used to kill cancer cells. Radiation therapy can be performed in two ways depending on the characteristics of the cancer:

a) externally using a machine outside the body that sends a targeted beam of radiation toward the tumour

b) internally by injecting radioactive material directly into or near the cancer

- Chemotherapy: drugs are used to either kill cancer cells or stop them from dividing. There are a number of chemotherapy drugs available and the optimal choice depends on the characteristics of the cancer.

Depending on the circumstances, anal cancer may be treated using one or a combination of any of these treatment options.

Prognosis following a diagnosis of anal cancer

The outcome of treatment for anal cancer depends on the characteristics of the tumour and the patient themselves. Anal cancer is a serious disease but treatment can be very effective, especially if the cancer is detected early.

About half of all anal cancers are diagnosed before spreading beyond the anus. The five-year survival rate for these patients is approximately 80%. The five-year rate decreases to about 61% if anal cancer is diagnosed after spreading to nearby lymph nodes and 30% if the cancer has spread to other organs prior to diagnosis.

It is important to remember that survival statistics are based on the average of all patients diagnosed with a condition and may not reflect what may happen in individual cases. Multiple factors can determine patient outcomes. An in-depth discussion with your doctor can help to set expectations regarding your prognosis and outcomes of treatment.

HIV and anal cancer

HIV can increase the risk of developing anal cancer. Treatment for anal cancer can further damage the weakened immune systems of HIV patients. For this reason, HIV patients with anal cancer are usually treated with lower doses of chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Rectal cancer

Malignant cells can form in the tissues of the rectum and this is called rectal cancer.