20 February 2016

Katherine Lawrenson’s third son Ryan was seven weeks old when she found out. That was last February, back when she had hair.

The 35-year-old is way outside the screening age band, had no family history and a healthy, active lifestyle. She does have one important risk factor, though – she lives in Cromwell.

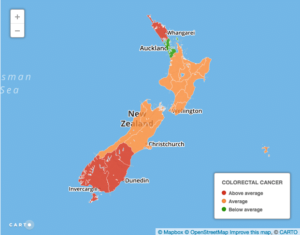

Whereas for most cancers, the highest death rates are in areas with high Maori and Pasifika populations and high poverty, the worst colorectal or bowel cancer statistics are in white and wealthy Southland, Otago and South Canterbury.

“I’ve got three kids, I can’t have cancer,” was Cromwell resident Katherine Lawrenson’s reaction when diagnosed with …

Supplied

“I’ve got three kids, I can’t have cancer,” was Cromwell resident Katherine Lawrenson’s reaction when diagnosed with terminal bowel cancer. Pictured here before treatment started, with sons Jayden, Ryan and Nathan.

About 18 months earlier, Lawrenson had been to her family doctor suffering from exhaustion. Her iron levels were rock bottom. Not knowing anaemia was a bowel cancer symptom, she took supplements and thought nothing of it. Her partner’s sister went to a different GP and was also found to have uncommonly low iron levels. Her GP undertook further tests and discovered bowel cancer. For Lawrenson, that 18 months could have been the difference between life and death.

Instead, like a third of colon cancer sufferers, she was only diagnosed when she turned up to a hospital emergency department in crippling pain. She had visited three different doctors a month earlier with severe, unyielding stomach pain. Two prescribed indigestion tablets.

“It was absolutely terrifying,” Lawrenson says. The cancer had already spread to her liver and lymph nodes. That means stage four – terminal. She had surgery and chemo, with $25,000 worth of unfunded Avastin, paid for largely from health insurance.

A year on, her scans are clear but she’s on a time-buying chemo regime which gives her seven or eight “reasonably functional” days out of 14. Six-year-old Jayden hates it when Mummy has to have her yucky medicine.

“It’s hard. You look at their little faces and it just breaks your heart.”

Lawrenson and her sister-in-law’s experience shows treatment differences can decide whether someone lives or dies. Access has also been a problem historically – a 2010 audit found Otago DHB had the lowest rate of colonoscopies, a critical diagnostic tool – across all DHBs.

In 2014, Southern DHB rejected one in three GP referrals for colonoscopies. Southern DHB says all referrals meeting national criteria are accepted and it now exceeds Health Ministry waiting time targets for colonoscopies.

But experts say there’s more to it than treatment differences. They’re just not sure what. Possible explanations have included high red meat consumption, vitamin D deficiency, Scots heritage and toxins affecting your gut bugs.

Otago University cancer epidemiologist Associate Professor Brian Cox even has a school milk theory. Calcium supplements can reduce bowel cancer risk in adults, so maybe a half pint bottle of full cream milk helped protect Kiwi kids from later contracting the disease.

What’s interesting is that the risk seems to be set before your 25th birthday. And people born in one era have different risk at the same age to people born in later periods. So if it’s related to diet, it could be set by what you eat as a child, or even what your mother ate in pregnancy, Cox says.

To confuse matters further, Maori have lower rates of bowel cancer, despite having generally higher levels of poverty and therefore eating less of the much-vaunted five-plus-a-day fruit and veges.

“Is it a poorer diet in terms of nutrition or a poorer diet in terms of whether it causes bowel cancer?” Cox asks.

While no-one can definitively explain the high southern death rates, experts do know how to fix them. The landmark, large-scale PIPER study – which released initial results last year – found nearly a quarter of New Zealand colon cancer cases were already incurable at diagnosis.

“We are picking it up late, which means we need strong emphasis on the diagnostic part,” says Chris Jackson, Otago University medical oncologist, Cancer Society chairman and PIPER researcher.

The answer, says Bowel Cancer New Zealand spokeswoman Mary Bradley, is national screening. Bowel cancer is treatable and beatable, if caught early, she says.

Diagnosed with bowel cancer herself at 28, Bradley is angry that the Government continues to stall on the issue. A pilot has been running in Waitemata – which has the third lowest bowel cancer death rate – since 2011, while New Zealanders in the worst affected areas are still awaiting free screening. The pilot has already picked up 257 cases of silent, symptomless bowel cancer and identified many more pre-cancerous polyps.

“With 1200 people dying every year, 100 every month, it just seems horrific that this is still happening. Quite unconscionable,” Bradley says.

And despite Southern DHB insisting everyone who meets national colonoscopy screening criteria gets one, Bradley talked last week to an Otago patient who was turned down for a colonoscopy and was now receiving private chemotherapy for Stage 3 bowel cancer.

Jackson agrees there’s a strong case for national screening. The PIPER study showed life-prolonging chemotherapy is also underused, being taken by less than 50 per cent of patients with advanced disease. However, unfunded drugs are not a major issue for bowel cancer, as they offer only “a modest additional benefit”, Jackson says.

For Lawrenson, chemotherapy was a no-brainer. It’s already bought her a year – time enough to organise a wedding. She and Jarred will wed next month at Carrick winery. Her brother is paying as the couple are skint after paying for her unfunded drugs.

*Statistics are for 2010-2012. Cancer death rate map shows areas with rates significantly higher or lower than the national rate, calculated using the Keyfitz method.

– Stuff