After five years of trialling and planning, New Zealand starts to see bowel screening introduced to the wider population this month. General practice is crucial to the success of the programme. Virginia McMillan finds out what it means for practices and their older patients

Far from being struck down with anxiety about the “C” word, most patients appreciate the call from their GP or practice nurse informing them of a positive faecal blood result.

That’s Hobsonville Family Doctors’ experience being part of the Waitemata DHB bowel screening pilot, nurse manager Brenda Gordon says.

“They’re usually quite receptive and pleased that you are interested in ringing them up,” Ms Gordon says.

“We have had a couple of patients whose sample was positive, who have gone on to have…early cancer removed. It makes them feel good that this service is available to them, and is working.”

The faecal immunochemical test (FIT) that patients carry out at home has so far been limited mainly to the Waitemata pilot, begun in 2011. By 2020, bowel screening is to be expanded to at least 700,000 older New Zealanders, with the FIT the key first step.

Easy and discreet

It is easier and more discreet than many might fear. People quickly pop the small plastic dipstick into their faeces to obtain a sample, enclose it in the container provided, and send it back FreePost to the programme managers.

Welcome to the National Bowel Screening Programme. For residents of Hutt Valley and Wairarapa, it starts any day now; Counties Manukau and Southern are next in line in the year ahead.

The clinical director of the ministry’s bowel cancer team, University of Auckland associate professor and internal medicine specialist Susan Parry, says: “It’s a day we have awaited for a long time – the launch of a national screening programme for a cancer that’s a significant contributor to deaths for our country.

“So we shouldn’t overlook the significance and importance of what is about to begin.”

Just over 3300 people were diagnosed with colorectal cancer in New Zealand last year, and 1252 people died from the cancer in the most recent year for which data are available (2013).

No other screening programme relies on GPs the same way

Auckland gastroenterologist Alasdair Patrick points out that no other screening programme relies on GPs in the way the bowel screening programme will.

“You guys will start to get patients getting the invitations in the mail and asking questions,” Dr Patrick told attendees of the GP CME in Rotorua last month.

The Waitemata pilot found that patients thought it critical for the GP to be involved. Patients who are anxious or reluctant to take part, or who have comorbidities, will benefit the most from a GP consultation, Dr Patrick says.

He believes it’s vital GPs promote and endorse the programme to their patients; encourage minority group participation (‘Race’ flag raised in talks on better deal for Maori from bowel screening, page 3); encourage those who have not sent in the sample, to do so; and inform the programme of patients who are ineligible (see “Who should not be screened?”, below).

Mention to older patients

John McMenamin, GP lead for the programme, suggests practice teams mention to their older patients when the programme is about to arrive in their area, and let them know what’s involved. In Hutt and Wairarapa, PHOs have been briefing general practice teams in education sessions; resources are also available online (see “Guidance, resources and background”, on this page).

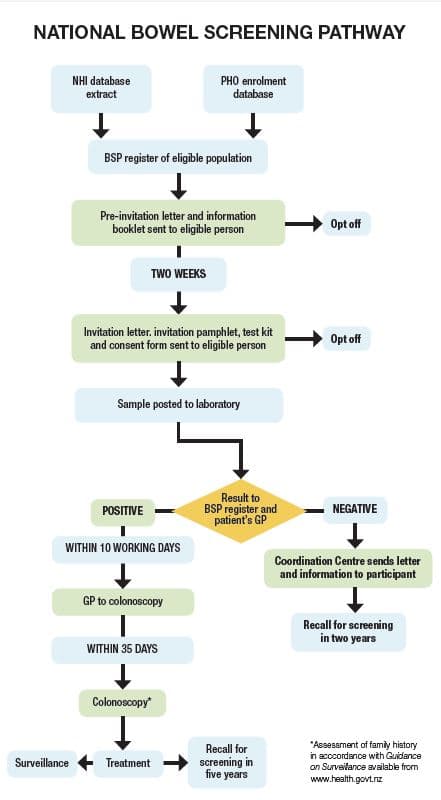

As a DHB district comes on board, the programme will start dispatching letters with patient information booklets to all residents aged 60 to 74, gradually, over a two-year period, depending on their birthdates (evens in year one, odds in year two).

Two weeks after the letter, people will be sent a package containing the test kit, instructions and consent form.

The FIT kit may be binned, ignored, overlooked or incorrectly used by some.

Anticipating 60 per cent participation

In the Waitemata pilot, the first round of invitations got a 56.8 per cent participation rate; the acceptable minimum internationally is 45 per cent, according to the ministry. Dr McMenamin is anticipating 60 per cent or higher in the programme.

He says this will be supported by publicity campaigns and local awareness-raising targeted to key population groups.

In the first two years, a prompt or reminder attached to the medical records will denote a patient is eligible. It’s hoped clinicians will use these reminders opportunistically to encourage participation.

Waitemata DHB’s programme team is managing the process, but a national coordination centre will be set up next year. Auckland DHB’s LabPLUS is contracted to test the samples, also until the end of this year. (A provider has not been decided beyond December.)

The programme sends all patients’ results to the GP inbox, with a letter to patients only in the case of negative results.

Dr McMenamin stresses the importance of the GP or practice nurse’s conversation with the person with a positive test result.

“When the test is positive, likely to be in seven out of 100 cases, the practice is expected to contact the patient, and invite them in for a conversation about the nature of the positive result and referral to colonoscopy.”

GPs will know the appropriate response to a positive test

GPs understand their patients well, so will know the appropriate response to a positive test, he says. A face-to-face consultation is expected for most; some patients may be fine discussing it in a phone consult. The fee payable to the practice for managing a positive result is $60 plus GST.

Screening will likely lead to about one additional consultation every several months for most GPs, Dr McMenamin says.

The programme’s Quick reference guide for GPs and patient information booklet can guide the content of the consult.

Referral should be made within 10 days of receiving the positive result, using the electronic, pre-populating form that arrives with it. The colonoscopy must take place within 35 days of a positive result reaching the GP.

Referrals prompt the DHB screening unit to arrange a colonoscopy.

Responsibility for notifying result lies ultimately with programme

Dr McMenamin says: “The responsibility for notifying the result belongs ultimately to the programme.

“We want the GP to have the consultation but, if they can’t contact the patient or they don’t respond, the programme will pick it up after 10 working days.”

It’s desirable to include family history information on the referral form but, if it’s not there, the screening unit will check it with the patient.

Some patients receiving the invitation will want to discuss it with their GP, Dr McMenamin says.

“Any opportunity to discuss the bowel screening programme is also an opportunity to update family history, whether in the screening age group or outside it.”

A patient’s family history may mean they are eligible for surveillance colonoscopy or for genetic testing, independently of the programme, he says. (See “Guidance, resources and background”.)

A lot of additional work for DHBs

Beyond the GP door, the programme creates a lot of additional work for DHBs. Dr Parry says Hutt Valley and Wairarapa DHBs were advised a year ago of numbers to plan for.

About 15,000 invitations will go out to Hutt and Wairarapa residents in the first year, out of a total of some 30,000 eligible people.

In the first year in the Hutt, 305 people can be expected to test positive and undergo colonoscopy; in Wairarapa, it’s estimated 128 will do so. The numbers are similar in the second year, and decline thereafter. Surveillance colonoscopy will be needed for a handful of patients this year, and across the two districts the number will reach 125 by 2020/21.

In a statement, National Screening Unit clinical director Jane O’Hallahan says criteria for DHBs include ability to undertake screening colonoscopies while also meeting wait-time indicators for other colonoscopies. Having considered the recent performance of Hutt Valley and Wairarapa DHBs, the ministry is confident they can manage the volumes, Dr O’Hallahan says.

DHBs are also expected to manage the histology arising from the programme.

Seventy per cent of people referred for colonoscopy are expected to have polyps, in many cases small ones (under 2mm) that can be removed at the time.

All suspect tissue will be biopsied for analysis.

The expected rate of a positive cancer finding from colonoscopy is 7 per cent, and most of these people will need treatment.

500 to 700 extra cancers a year

The first two years in any area will produce a “hump” of cancers, 20 to 25 per cent more than normally detected, Dr Parry says. It’s expected this will mean 500 to 700 extra cancers a year nationally in the programme’s early years.

Lives will be saved by earlier detection and treatment, she says. It will eventually translate to reduction in mortality in the age group offered screening.

“In time, when enough people have been screened for long enough, and enough colonoscopies with removal of polyps have been carried out, we will also get a decrease of incidence of bowel cancer in the population offered screening.”

International experience has shown bowel screening reduces mortality by between 16 per cent and 22 per cent after eight to 10 years.

Dr McMenamin says most GPs will have had patients presenting late, losing quality of life and dying early. He’s looking forward to that changing.

Colonoscopy workforce issues

• Gastroenterologists, general surgeons and nurse endoscopists can carry out colonoscopies.

• An additional three trainee gastroenter-ologists have been taken into training each year since 2013.

• Up to six nurse endoscopists can be trained each year, and it’s expected at least four nurses a year will go through the training. Four are undertaking it this year.

• Auckland, Southern and Hutt Valley DHBs are working with existing staff to bring them up to the prerequisite level.

• Additional funding for colonoscopy services, to reduce waiting times and ensure progress on delivering colonoscopies is sustained, has been provided to DHBs since 2013/14. Funding announced last December took the total to $19 million.

• In 2013, 29,030 outpatient diagnostic colonoscopies were performed. The numbers performed have increased each year, with almost 40,000 performed in 2016.

• Increased awareness of bowel cancer tends to lead to more referrals of symptomatic patients, another factor for colonoscopy workloads that DHBs must juggle.

• Ministry of Health bowel cancer team clinical director Susan Parry says the number of people waiting outside the target time frame has halved in the past three years.

Who should not be screened?

As advised in the patient information booklet, those who should not have bowel screening through the programme are those who:

• have symptoms of bowel cancer

• have had a colonoscopy within the last five years

• are on a bowel polyp or bowel cancer surveillance programme

• have had or are currently being treated for bowel cancer

• have had their large bowel removed

• are currently being treated for ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease, or

• are seeing a doctor about bowel problems.

Programme GP lead John McMenamin says people can exclude themselves based on the information in the booklet. The GP is expected to refer all patients with a positive FIT result to the colonoscopy screening unit. “Where colonoscopy is contraindicated, the referral will be considered an information referral.”

Source NZ Doctor